The origin of heliocentrism

The central fire

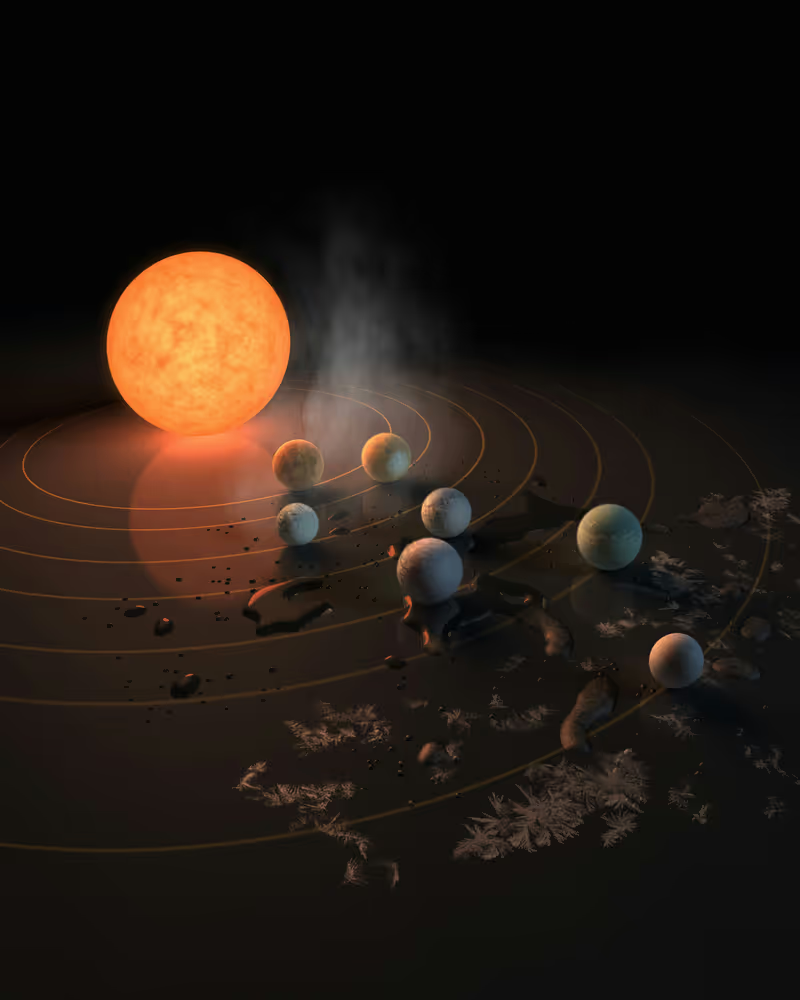

The Pythagoreans are not only involved in the invention of a spherical world, but also in the invention of heliocentrism. Heliocentrism teaches that a great fire/light, namely the sun, occupies the center of the cosmos. This idea originated with Philolaus, a Pythagorean of the fifth century B.C. Philolaus proposed that the world was not stationary, but in motion around a central fire he called the Hearth (also Hestia) of the All; the sun also revolved around this fire. His mystical notions directly influenced later thinkers who decided to give this central position to the sun instead, producing as a result a solar system or sun-centered system. The most prominent example of this is Nicolaus Copernicus, who will be discussed in a later section:

Heliocentrism, a cosmological model in which the Sun is assumed to lie at or near a central point (e.g., of the solar system or of the universe) while the Earth and other bodies revolve around it. In the 5th century BC the Greek philosophers Philolaus and Hicetas speculated separately that the Earth was a sphere revolving daily around some mystical “central fire” that regulated the universe. . . .

The heliocentric, or Sun-centred, model of the solar system never gained wide support . . . .

. . . it was not until the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri VI (“Six Books Concerning the Revolutions of the Heavenly Orbs”) in 1543 that heliocentrism began to be reestablished. (Britannica, “heliocentrism”)

Philolaus was the first Greek philosopher to suggest that the Earth was not the center of the universe but a planet like any other and that all the planets, the Sun, and the Moon, revolved around a central fire . . . . His beliefs are thought to have influenced Plato, Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE), and Aristarchus of Samos (l.c. 310 to c. 230 BCE), who first advocated for a heliocentric model of the solar system. (Mark, “Philolaus”)

The planets all moved around the central fire from west to east, each with their own revolution, most of them revolving slowly but Earth completing a rotation in 24 hours. (Mark, “Philolaus”)

Philolaus has located the fire in the middle, the center; he calls it Hestia, of the All, the Guardpost of Zeus, the Mother of the Gods, the Altar, the Link, and the Measure of Nature. . . . The center, says he, is by its nature the first; around it, the ten different bodies carry out their choral dance. These are: the heaven, the planets, lower the sun, and below it the moon; lower the earth, and beneath this, the counter-earth, then beneath these bodies the fire of Hestia, in the center, where it maintains order. (The Pythagorean Sourcebook)

The Pythagorean Philolaus locates the fire in the center一it is the Hearth (Hestia) of the All . . . . (The Pythagorean Sourcebook)

Some insist that the earth is immovable; but the Pythagorean Philolaus says that it moves circularly around the central fire, in an oblique circle like the sun and moon.

. . . The Pythagorean Philolaus says that the sun is a vitrescent body which receives the light reflected by the fire of the Cosmos, and sends it back to us, having filtered them, light and heat . . . . (The Pythagorean Sourcebook)

The Pythagorean [cosmological] system was finally reorganised by Philolaus, who took the momentous step of moving the earth from its position in the middle, and replacing it by a central fire, the ‘hearth of the cosmos’ . . . . (Wright)

Late in the 5th century [B.C.], or possibly in the 4th century [B.C.], a Pythagorean boldly abandoned the geocentric view and posited a cosmological model in which the Earth, Sun, and stars circle about an (unseen) central fire—a view traditionally attributed to the 5th-century [B.C.] Pythagorean Philolaus of Croton. (Thesleff)

The Monad and the Hearth

The supreme god of the Pythagoreans was the Monad, an abstract entity represented spherically and corresponding to the number one. From its center, the Monad projected outward all of the cosmos, thus situating itself at the center of all things, like the Hearth. This similarity with the Hearth was not coincidental. In Pythagorean philosophy (Pythagoreanism) the Monad was identified with the Hearth:

. . . the Pythagorean Philolaus conceived the One [Monad] as “the first principle of all things”. Moreover, in the cosmology of the same Pythagorean [Philolaus], the One [Monad] is the unified principle in the center of the sphere identified with the central fire: the hearth. (Stamatellos, Plotinus and the)

In this context, it looks as though the disciples of Empedocles and Parmenides and just about the majority of the sages of old followed the Pythagoreans and declared that the principle of the monad is situated in the middle in the manner of the Hearth, and keeps its location because of being equilibrated . . . .” (Iamblichus)

This “hearth” is the central fire and sits like the monad in the sphere [center] of the observable universe and, when divided like the monad, gives birth to the perfect ten of the planets. (Mark, “Philolaus”)

The Monad was also associated with the Greek fire god Prometheus and sun god Apollo:

That is why it [the Monad] is called ‘artificer’ and ‘modeler,’ since in its processions and recessions it takes thought for the mathematical natures, from which arise instances of corporeality, of propagation of creatures and of the composition of the universe. Hence they call it [the Monad] ‘Prometheus,’ the artificer of life . . . . (Iamblichus)

The Pythagoreans embellished numbers and figures with appellations related to the gods. According to Plutarch, the Monad was identified with Apollo, the sun god, and it is noteworthy that Pythagoras himself had the name ‘Hyperborean Apollo’. The Pythagoreans also identified the Monad with the hearth fire at the centre of the universe. (Stamatellos, Introduction to Presocratics)

As Plutarch testifies, the Pythagoreans embellished numbers and figures with the appellations of the gods. The Monad was identified with Apollo . . . .

The figure of Apollo, the Sun God, plays a central role in the Pythagorean tradition. It is significant that Pythagoras himself had the name “Hyperborean Apollo”. This is also testified by Iamblichus in De Vita Pythagorica, who reports that Pythagoras was given the name of the Hyperborean Apollo by the people of Croton. Apollo was well known in Greek mythology for his connection to and identification with the sun. For the Pythagoreans the One [Monad] was also equated with the element of fire: the central fire of the universe. This makes the analogy between the One [Monad] and Apollo even more evident. (Stamatellos, Plotinus and the)

What emerges with absolute certainty about the Pythagorean tradition of theology is that the deity most honoured within it, already from its founder’s own time, is Apollo . . . . Pythagoras himself was unequivocally assimilated to him in an oral saying, and perhaps also, more enigmatically, in the reported story that made him a reincarnation of Euphorbus, a hero of the Iliad with Apollonian features. (Ancient Philosophy of)

However, Aristotle in his lost monograph On the Pythagoreans emphasized how Pythagoras was seen at two places at once, how he showed his golden thigh, how he was thought to be the Hyperborean Apollo, and how he was addressed by a certain river. Obviously these stories are not “late Neopythagorean inventions” but go back to the time of Plato or before. (The Pythagorean Sourcebook)

In Greek mythology, Hyperborea was the land located to the far north of the known world and it was so remote it was considered even beyond the North Wind. There[,] a legendary race known as the Hyperboreans lived and worshipped the sun god Apollo. (Cartwright)

Pythagoras’ father was Mnesarchus, a Tyrrhen who earned his living as a merchant and shipowner. His livelihood took him throughout the islands of the Mediterranean, often with young Pythagoras aboard. Originally, Pythagoras’ mother was called Parthenis, the Virgin. . . . As it turns out, while Mnesarchus was off on one of his long voyages, Parthenis was secretly seduced by Apollo. Afterwards she was renamed Pythais, in honor of Apollo, who had destroyed the python guarding the oracle at Delphi, making the place his own.

Pythagoras had proof of his Heroic birth, and revealed this proof whenever it was to his advantage: upon his left thigh was a vast golden birthmark. Birthmarks were believed by the Greeks of the time to be a sign of divinity. Gold was associated with Apollo and thus the golden birthmark was accepted as proof of Pythagoras’ relationship to this radiant god. (Pennington)

Even in his own time, Pythagoras was a legend. Rumored to be the son of the god Apollo by a virgin birth to his mother, Pythais, he was said to have worked miracles, conversed with daemons, and heard the “music” of the stars. He was regarded by his followers as semidivine, and there was a saying that “among rational creatures there are gods and men and beings like Pythagoras.” (Wertheim, Pythagoras’s Trousers: God)

. . . first and foremost, Pythagoreanism was a religion. Specifically, it was an ascent religion. Through a strict regimen of bodily and spiritual purification, and by careful study of mathematics, the religion of Pythagoras promised unmediated experience of the All. In other words, gnosis—that union with divinity that is characterized by a state of intuitive all-knowingness. For Pythagoras the source of divinity, the fountainhead of the All, was the supreme godhead of the number One [Monad], which he associated with the sun god Apollo. . . .

. . . the Pythagorean spirit was a major catalyst for the emergence of modern physics during the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century—and has remained a force within that science ever since. All the talk from TOE [theories of everything] physicists today about “the mind of God” is but a diluted residue of the Samian master’s [Pythagoras] powerful brew of mathematical mysticism. (Wertheim, The Pearly Gates)

The mark which signifies the monad is a symbol of the source of all things. [6] And it reveals its kinship with the sun in the summation of its name: for the word ‘monad’ when added up yields 361, which are the degrees of the zodiacal circle. (Iamblichus)

His [Apollo] forename Phoebus means “bright” or “pure,” and the view became current that he was connected with the Sun. (Britannica, “Apollo”)

He [Apollo] became associated with the sun, and was even identified with Helios, the sun god. Also associated with healing, he [Apollo] was the father of Asclepius. (Britannica, “Apollo summary”)

The mythic Apollo was a symbol of light, whence he was called also Phoebus and Helios. He appears to have been thus regarded in very early times by the Hyperboreans, and is said to have been identical with the Egyptian Horus, the god of the burning sun. (Millington)

. . . [Philolaus] claimed that fire was the first cause of existence and heat the underlying source of human life. He is best known for his pyrocentric model of the universe, which replaced Earth as the center of the solar system with a central fire, around which all else revolved. (Mark, “Philolaus”)

It is noteworthy that from an early beginning Pythagoras was honored as a son of Apollo and as “Hyperborean Apollo,” suggesting that fire (as it relates to the burning sun or Apollo) and light were important symbols to the Pythagorean tradition before Philolaus introduced his pyrocentric cosmology. Although Philolaus’ cosmology did not gain wide support at the time, it would play a crucial role later in the development of modern cosmology.

The Monad/Hearth and Egypt

A curious parallel to these philosophies is found in ancient Egypt, before the time of Pythagoras. The ancient Egyptians exalted their sun god Atum above all the others, calling it “the One” or “the All,” terms also employed by the Pythagoreans to describe the Monad and Hearth. Egyptian solar theology was likely transmitted to Pythagoras during a long sojourn in Egypt, in which he sought the wisdom of Egyptian priests. Although ancient Egyptian cosmology consisted of a flat stationary world, the predominant theology centered heavily on the sun:

The sun was conceived as a sphere that, on occasions, might need wings or a beetle to propel it across the heavens. It was regarded as an eternal and self-renewing force that consistently appeared on earth at dawn and disappeared again at sunset. In the Egyptian universe, this daily cycle was the most important natural event, and the other elements of creation were only present as a setting for the culminating act of creation – the first rising of the sun. (David)

The created world consisted of land below and sky above which were separated from each other by the atmosphere. The sky formed an interface [a divide or boundary] between the land and the limitless ocean beyond. Within the created world, daily existence was ordered by the rising and setting of the sun . . . . (David)

The biographies of Pythagoras are unanimous that at an early age he travelled widely to assimilate the wisdom of the ancients wherever it might be found. He is said by lamblichus to have spent some 22 years in Egypt studying there with the priests . . . . These accounts are generally accepted by most scholars—as indeed they should be, owing to the high degree of contact between Asia Minor and other cultures . . . . (The Pythagorean Sourcebook)

In classical antiquity the topos of a trip to Egypt was an especially common one. In the fifth century B.C.E., Herodotus reported that Solon and Pythagoras had been in Egypt. Returning to Greece, Pythagoras brought back certain temple rituals, the doctrine of the transmigration of souls, and, with the myth of Typhon or Seth, the dualistic concept of the world. Isocrates also records that Pythagoras made a stay in Egypt and brought philosophy back to Greece. In the first book of his Bibliotheca historiae, Diodorus records a whole series of Greek culture heroes who traveled to Egypt to “partake of the customs and sample the teaching there,” which they introduced into Greece. Orpheus “brought away from there the greatest part of his mystical rites [. . . and] his fables about the souls in Hades. [. . .] Lycurgus also, as well as Solon and Plato are reported to have inserted many of the Egyptian customs into their codes of law, while Pythagoras, they say, learned from the Egyptians the doctrine of divine wisdom, the theorems of geometry, the theory of numbers, and in addition, the transmigration of the soul into every living being.”

Since the Egyptians were considered schoolmasters of the Greeks, superior in wisdom, it seemed opportune to refer to their knowledge. . . . because of its primacy in antiquity and civilization, Egypt is the highestranking source of information. Iamblichus uses the model of interpretatio graeca, which understood foreign cultures as alternative forms of expression, to uncover an Egyptian-Hermetic core in Greek culture. If Greek philosophy is genetically linked to Egyptian theology and wisdom, it is possible to understand the conceptual world of Egypt as the latent background of Greek culture. (Ebeling)

Different [Egyptian] temples had different specialities. If Pythagoras did not move on too quickly from Heliopolis [Egypt] (in Porphyry’s scenario) he might have learned a creation theology that explained the diversity of nature arising from a single source, the god Atum, meaning ‘the All’. Atum existed in a state of unrealised potential not far different from the ‘unlimited’ in Anaximander’s teaching and later in Pythagorean thinking. (Ferguson)

Equally important, the conceptualization of Atum represents the earliest example of humans developing an ontology or metaphysical philosophy to explain the nature of being and existence. . . .

The word Atum has been variously translated by Egyptologists as “The All,” “The Complete One,” and the “Undifferentiated One.” The word is also a variation of the Egyptian verb tm, meaning “to not be,” communicating the ideas of preexistence and precreation. (Encyclopedia of African)

The t(u)m of Atum’s name can be translated ‘not to be’ and ‘to be complete’, so there are several interpretations of the god’s name, most commonly ‘the all’/‘the complete one’, but also ‘he who is not yet complete’. Another scholar favours ‘the undifferentiated one’, the idea being that Atum contained within himself the life force of every other deity (male and female) yet to come into being. He held the title ‘Lord to the Limits of the Sky’, and was regarded very much as a solar deity . . . . (Wilkinson)

Atum, in ancient Egyptian religion, one of the manifestations of the sun and creator god, perhaps originally a local deity of Heliopolis. (Britannica, “Atum”)

The main city where Atum was worshiped was called “Helio-polis,” borrowing the name of the Greek sun god Helios (Britannica, “Helios”); the terms “heliocentrism” and “heliocentric system,” synonymous with “solar system,” are also etymologically related:

Heliopolis, one of the most ancient Egyptian cities and the seat of worship of the sun god . . . . (Britannica, “Heliopolis”)

Like the Monad/Hearth, Heliopolis (representative of the sun god) was viewed as occupying an important central position:

According to the ancient priests of Heliopolis, Atum was the monad—the original fountainhead, or source, from which the other gods sprang. The priests also claimed that when Atum fashioned the benben, or “mound of creation,” that first piece of dry land rested in the very center of Heliopolis itself. So many Egyptians believed that Heliopolis lay at the center of the world. (Nardo)

A similar theological pattern is observed later in ancient Egyptian history, with the god Aten, another manifestation of the sun:

In ‘Theological Responses to Amarna’ (2004), German Egyptological heavyweight Jan Assmann showed how the process began in the fourteenth century BCE when Akhenaten ascended to the throne. . . . he banned the entire Egyptian pantheon and replaced it with a single figure: Aten, the personification of the disc of the sun, or of solar energy. Anticipating the earliest pre-Socratic thinkers [philosophers], who in various ways traced the source of the cosmos to a single element, Akhenaten promulgated that solar energy was not only divine, it was the sole element out of which the entire universe evolved. . . .

. . .

The priesthood answered Akhenaten’s monist challenge in a way that prefigured Hermetic, and perhaps even ancient Greek efforts, such as those of Parmenides and his followers, to uncover the oneness concealed behind the plurality of the visible world. The Egyptian priesthood revamped older ideas to posit a hidden divine entity, symbolized by the sun, as constituting and animating the universe. Struggling with the limited vocabulary of their time, priests tried alluding to this unknowable Supreme Being’s immaterial qualities by loosely naming it ‘One’, ‘hidden’, and ‘soul-like’. They claimed that it was inaccessible to language or intellect and inhabited a separate ontological space. Paradoxically, the same priests also averred that the millions of gods and other constituents of the universe were constantly evolving parts of this ineffable being, which remained present yet invisible in and as the cosmos. (Flegel)

Pythagorean philosophy was known for being very welcoming to foreign beliefs, incorporating and building upon them:

Iamblichus’ On the Pythagorean Life seeks to establish Pythagoreanism as an exemplary way to do philosophy, yet an important objective for Iamblichus’ Pythagorean project is also the inclusion of multiple traditions into Pythagoreanism:

In general, they say Pythagoras was a zealous admirer of Orpheus’ style and rhetorical art, and honored the gods in a manner nearly like Orpheus’, setting them up, indeed, in the bronze of statues, not bound down with our human appearances, but with those divine rites of gods who comprehend and take thought for all things, and who have a substance and form similar to the All. He proclaimed their purificatory rites and what are called “mystic initiations,” and he had most accurate knowledge of these things. Moreover, they say that he made a synthesis of divine philosophy and worship of the gods, having learned some things from the Orphics, others from the Egyptian priests; some from the Chaldeans and the magi, others from the mystic rites in Eleusis, Imbros, Samothrace, and Lemnos, and whatever was to be learned from mystic associations [or from the Etruscans]; and some from the Celts and Iberians.

Iamblichus’ terminology here is far from random. For Iamblichus, Pythagoreanism is a synthesis of multiple traditions that mirrors the unity of the multiplicity of beings in the noetic and cosmic order. In Platonic terms, Pythagoras applied the aphaeretic dialectical method to the traditions he encountered, analyzing each in order to synthesize their common traits, which he distilled into sayings, symbols, and rituals. Having learned from the wisest traditions, Pythagoras became an intermediary guide to help other philosophers in turn become godlike . . . . (Brill’s Companion to)

Renaissance men saw Pythagoras as living in a period of rather easy cultural exchange: he traveled to Egypt to study the virtues of numbers and geometry, and then to Babylon, where the Chaldeans taught him the course of the planets. Pythagoras then wandered in Persia and India, and then back to Calabria. Early modern scholars perceived his itinerary as potentially recovering a synthesis of ancient wisdom. (Ben-Zaken)

Whatever Pythagoras received, however, he developed further . . . . He was the first to give a name to philosophy, describing it as a desire for and love of wisdom . . . . (The Pythagorean Sourcebook)

Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus is hailed as the father of “Helio-centrism.” He appears two thousand years after Pythagoras, in the sixteenth century:

. . . [Copernicus] proposed that the planets have the Sun as the fixed point to which their motions are to be referred . . . . This representation of the heavens is usually called the heliocentric, or “Sun-centred,” system—derived from the Greek helios, meaning “Sun.” Copernicus’s theory had important consequences for later thinkers of the Scientific Revolution, including such major figures as Galileo, Kepler, Descartes, and Newton. (Westman)

In 1543, Copernicus published his proposed system for the world in a book, in which he states:

. . . they [the philosophers] are in exactly the same fix [problem] as someone taking from different places hands, feet, head, and the other limbs—shaped very beautifully but not with reference to one body and without correspondence to one another—so that such parts made up a monster rather than a man. . . .

. . . I began to be annoyed that the philosophers, who in other respects had made a very careful scrutiny of the least details of the world, had discovered no sure scheme for the movements of the machinery of the world . . . . (Copernicus)

Some think that the Earth is at rest; but Philolaus the Pythagorean says that it moves around the fire with an obliquely circular motion, like the sun and moon. (Copernicus)

Evidently, Copernicus was familiar with Philolaus and his teaching of the Hearth and he uses it in defense of his own cosmological system. In Copernicus’ system, however, the Hearth was replaced with the actual sun:

. . . [Copernicus] quoted from various followers of Pythagoras, even though they did not actually support his theory . . . . Platonists looked back to Pythagoras as the font of wisdom, and so Copernicus quoted from his followers . . . . (Hannam)

Several scholars of the subject admit this important development:

In the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus’s (1473–1543) view that the sun is at the center of the universe was often called the “Pythagorean hypothesis,” . . . . (Galileo Goes to)

The association of Copernicus’s ideas with the ancient central fire cosmology of Pythagoras was more than a dismissal of the antiquity of heliocentrism; it was especially damning, inasmuch as it implied other shared heresies [beliefs of the Pythagoreans] . . . . (Galileo Goes to)

The atmosphere of Copernicus’s work is not modern; it might rather be described as Pythagorean. (Russell)

Thus, among preAristotelian philosophers, it was held by the Pythagoreans that fire is at the centre of the universe . . . . Such views, held only by a minority, were generally regarded in antiquity and later as impious and absurd, yet many of them were incorporated into the new Copernican cosmology. (Rivers)

Philolaus was the precursor of Copernicus in moving the earth from the center of the cosmos and making it a planet, but in Philolaus’ system it does not orbit the sun but rather the central fire. The astronomical system is a significant attempt to try to explain the phenomena but also has mythic and religious significance. (Huffman)

For Philolaus, the world order included fire at the centre, rather than the Earth. The association of Pythagoreanism with a non-geocentric universe continued into the early modern period, when in 1543 Nicolas Copernicus cited Philolaus as his precursor, in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) [his book] . . . . (Taub)

The Pythagorean thread is remarkable because it explicitly shows up in the works of many important figures in the Copernican Revolution, including Copernicus, Bruno, Kepler and Galileo. (Martinez, Burned Alive: Giordano)

Copernicus was so impressed by the Pythagoreans that he had planned to include the ancient Pythagorean letter from Lysis to Hipparchus in De Revolutionibus [his book]. Copernicus translated it from the Greek and included it in a draft, but for some reason he deleted it before the book was printed, though it was later found in his manuscripts. There, Lysis allegedly wrote:

I would never have believed that after Pythagoras’ death his followers’ brotherhood would be dissolved. But now that we have unexpectedly been scattered hither and yon, as if our ship had been wrecked, it is still an act of piety to recall his godlike teachings and refrain from communicating the treasures of Philosophy to those who have not even dreamed about the purification of the soul. For it is indecent to divulge to everybody what we achieved with such great effort, just as the Eleusinian goddesses’ secrets may not be revealed to the uninitiated. The perpetrators of either of these misdeeds would be condemned as equally wicked and impious . . . That godlike man [Pythagoras] prepared the lovers of philosophy . . . divine and human doctrines were promulgated by him.

This letter would have ended Book 1 of his De Revolutionibus. (Martinez, Burned Alive: Giordano)

Trismegistus

The Pythagoreans were not the only source Copernicus looked to for inspiration. In the same 1543 book, Copernicus cites an individual named Trismegistus:

In the center of all rests the sun. For who would place this lamp of a very beautiful temple in another or better place than this wherefrom it can illuminate everything at the same time? As a matter of fact, not unhappily do some call it the lantern; others, the mind and still others, the pilot of the world. Trismegistus calls it a “visible god”; Sophocles’ Electra, “that which gazes upon on all things.” And so the sun, as if resting on a kingly throne, governs the family of stars which wheel around. Moreover, the Earth is by no means cheated of the services of the moon; but, as Aristotle says in the De Animalibus, the earth has the closest kinship with the moon. The Earth moreover is fertilized by the sun and conceives offspring every year. (Copernicus)

Hermes Trismegistus was a mythic Egyptian of the distant past that at the time of Copernicus (the Renaissance) rose to fame. His ancient writings were re-discovered, translated, and he was recognized as a great philosopher of sorts; the writings are known as the Hermetic writings or Hermetica. The dating of these writings was later disputed in the seventeenth century and they were re-dated to the first centuries after Christ. With this revelation, the fame of the ancient philosopher gradually came crashing down. Today most scholars concur with this initial assessment made by Isaac Casaubon:

Yet by the early seventeenth century, the myth of Hermes Trismegistus had suffered a severe blow. . . . It was almost by chance that in 1614 the Huguenot scholar Isaac Casaubon, caught up in the struggle between Rome and Luther that led to the Reformation and reshaped the face of Christendom, realized that the Hermetic writings that had had such an immense influence over philosophers, theologians, and scientists were most likely forgeries — or in any case, were not what their many advocates believed they were. Casaubon discovered that they were not, as many believed, written in dim ages past, but had emerged in late antiquity, a product of the philosophical melting pot of Alexandria [Egypt] in the years following Christ. (Lachman, The Quest For)

Although for centuries Hermes Trismegistus was believed to have been a real person who lived at ‘the dawn of time’, and who received a primordial ‘divine revelation’ – the ‘perennial philosophy’ that is at the heart of much of western spiritual thought – he is now thought to have been a fictional figure, devised by the authors of the Hermetic writings, who lived in Alexandria in Egypt in the first few centuries after Christ. (Lachman, The Caretakers of)

. . . the earliest possible data, which come from the texts themselves (sometimes referring to one another and to Hermetica outside the Corpus), indicate that Hermetic collections of some kind circulated as early as the second or third centuries. (Copenhaver)

It is very likely that hellenized Egyptian priests produced the Hermetic writings as they do contain authentic Egyptian elements that would have been familiar to a priest; hellenized means that these priests had adopted Greek culture (“Hellenize”; “Hellenist”; “Hellenism”):

It was in ancient Egypt that the Hermetica emerged, evolved and reached the state now visible in the individual treatises. But this was not the Egypt of the pharaohs. Nectanebo II, the last pharaoh of the last dynasty, had already fled the Persian armies of Artaxerxes III when Alexander came to Egypt in 332 [B.C.] to found a city in his own name west of the Nile’s Canopic mouth. (Copenhaver)

In Egypt, in the midst of this cultural and spiritual turmoil, over the course of several centuries when the Ptolemies, the Romans and the Byzantines ruled the Nile valley, other persons unknown to us produced the writings that we call the Hermetica. (Copenhaver)

After the discovery of the Coptic manuscripts at Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt, stress shifted again to the genuinely Egyptian concepts in the Hermetic tractates. Connections could be made to temple inscriptions of rather late date, and even to statements in the most ancient mythological and theological texts. Today many scholars assume that the Hermetic writings should be attributed to hellenized Egyptian (temple-) priests who disseminated their theology through these texts. (Ebeling)

Around 200 CE the Christian writer Clement of Alexandria knew of “forty-two books of Hermes” considered indispensable for the rituals of Egyptian priests . . . (Copenhaver)

No hieroglyphic inscription can be dated later than the end of the fourth century CE. Coptic emerged in the third century when the church found it still necessary to use an Egyptian dialect but wanted it written in modified Greek letters. (Copenhaver)

The last known hieroglyphs were carved in 394 at Philae, where the worship of Isis survived until about 570. (Britannica, “Egyptology”)

The tradition that emerged from the Hermetic writings is called Hermeticism and, as discussed, is syncretistic in nature with supremacy placed on Egypt; syncretism entails a mixing of beliefs, similar to how Pythagoreanism operated:

Such doctrine was not peculiar to the Hermeticists. These ideas occur in ancient Egyptian thought, and in Greek philosophy of nature, and we find them systematically elaborated in, for instance, the Stoic concept of universal sympathy and in Neoplatonic [Greek] cosmology. It is characteristic, however, that this conglomeration of doctrines appears in the guise of an ageold wisdom of Egyptian origin, handed down as a revelation by Hermes Trismegistus to a select circle of spiritually and morally superior adepts.

The texts often stress that Hermes and his wisdom were Egyptian. This point becomes especially clear from the roles played by such major Egyptian deities as Isis and Horus in some of the Hermetic writings. (Ebeling)

Hermes’ epithet “Trismegistus,” literally the “thrice-greatest,” also has an Egyptian background. In Egyptian, the superlative was expressed by repeating the positive two or three times: “great and great and great” means “greatest” or “very great.” However, in the Greek Raffia decree of 217 BCE, Thot-Hermes is called “the greatest (megistos) and the greatest (megistos),” which later on must have led to the term “Trismegistos.” (Hermes Explains: Thirty)

The mention of Egyptian names and topoi [in the Hermetic writings] is so striking that we cannot dismiss them as mere “decor,” especially as parallels can be found in ancient Egyptian texts. Hermes’ ornamental epithet, “thrice great,” has unambiguously Egyptian precursors. From the second millennium B.C.E. on, Thoth was revered as the “twice great,” which was then escalated into “thrice great,” that is, “greatest of all,” and finally became “Trismegistus” in the Greek language. (Ebeling)

Trismegistus himself is a fusion of the Egyptian god Thoth with the Greek god Hermes:

It was to this powerful [Egyptian] god [Thoth] that the Egyptian Hermeticists [priests] of the second and third centuries A.D. joined the image and especially the name of the Greek [god] Hermes. From this time onward the name “Hermes” came to denote neither Thoth nor Hermes proper, but a new archetypal figure, Hermes Trismegistus, who combined the features of both.

. . . The Hermes that concerns us is primarily Egyptian, to a lesser degree Greek, and to a very slight extent Jewish in character. (Hoeller)

A contemporary of Moses

Before his loss in popularity, Trismegistus was touted as a contemporary of Moses, which earned him respect among Christians. His inventors were also familiar with Judaism as they emulated ideas from it. This afforded his writings the guise of being “Christian” also:

It is vital to an understanding of the historical role played by the hermetic texts to note that, at the time of the Renaissance, their words were widely believed to have been written in the extremely dim past—before the birth of Christ and before the time of Plato and Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.), and their author was sometimes thought to have been a contemporary of Moses, the accepted author of the biblical Book of Genesis. (Encyclopedia of the)

By making him a contemporary and ally of Moses, it made the figure more appealing and acceptable to various groups. Not only this, but Moses was the author of Genesis. If Trismegistus was his contemporary, he too must know a thing or two about the world. Cosimo de’ Medici (a wealthy banker of Florence, Italy) funded the project to translate the Hermetic writings, fascinated by the mystical cosmology contained in its pages:

Hermes [Trismegistus] was supposedly a contemporary of Moses, and the Hermetic writings contained an alternative story of creation that gave humans a far more prominent role than the traditional account. . . . Humans could imitate God by creating. To do so, they must learn nature’s secrets, and this could be done only by forcing nature to yield them through the tortures of fire, distillation, and other alchemical manipulations. The reward for success would be eternal life and youth, as well as freedom from want and disease. It was a heady vision, and it gave rise to the notion that, through science and technology, humankind could bend nature to its wishes. This is essentially the modern view of science, and it should be emphasized that it occurs only in Western civilization. (Williams)

In 1460, a monk, Leonardo da Pistoia, arrived in Florence from Macedonia with a Greek manuscript. Cosimo employed many agents to collect exotic and rare manuscripts for him abroad, and this was one such delivery. However, this particular manuscript contained a copy of the Corpus Hermeticum. Gleaning something of its mystical cosmology, the elderly Cosimo was convinced that the Hermetica represented a very ancient source of divine revelation and wisdom. In 1463, Cosimo told Ficino to translate the Hermetica before continuing his translation of Plato. (Goodrick-Clarke)

As a “Christian” philosopher, Trismegistus helped promote wider acceptance of Greek philosophy and present the tradition as not pagan, when in fact it was:

Furthermore, the patent coincidences with “later” Greek thought, especially with Platonism, were routinely interpreted as revealing Hermes to have been one of the teachers of the Greeks, while the Christian resonances similarly indicated that Plato’s philosophy was not genuinely pagan. (Encyclopedia of the)

Most notably, principal efforts were made by fathers of the Roman Catholic Church to achieve wider acceptance of Trismegistus within Christianity:

The ascertainment of commonalities between Hermeticism and Christianity by some of the Church Fathers would prove important to the history of the transmission of Hermetic ideas . . . . (Ebeling)

. . . the Church Fathers established doctrines in which they incorporated the language and the intellectual apparatus [philosophy] of Graeco-Roman culture. The Fathers responded to the conjecture that the Christians were responsible for the fall of the culture of the ancient world by pointing to a fundamental consensus of pagan philosophy and Christian dogmatics. For them, the differences between the best pagan philosophers and Christian doctrine were not irreconcilable. (Ebeling)

As the New Testament message was going out

The Hermetic writings were written in the first centuries as the New Testament message was going out. What better way for Satan to counter the message of Christ than by promoting rival writings that emulated ideas from Judaism. Of the places described in the Bible, “the wisdom of Egypt” (1 Kings 4:30) and “the wisdom of the Egyptians” (Acts 7:22) proved alluring to some:

What role did Hermes Trismegistus, this Egyptian sage, magus, and herald of a cosmic All-God, play in the Christian conception of the world? How could Thrice-great Hermes hold his own in a spiritual milieu stamped by biblical scripture and the authority of the Church Fathers? There is no mention of Hermes in the Bible, although the books of the New Testament must have originated at the same time that Hermetic texts were being written. For the Christian world, Hermes Trismegistus was first of all an Egyptian, and in late classical antiquity, for instance, in the writings of Iamblichus, Hermeticism was considered an Egyptian religion. Unlike Hermes, Egypt played an important role in the Old Testament. (Ebeling)

The Hermetica are full of random pieties, which is why Christians from patristic times onward so much admired them. (Copenhaver)

For Christians, it was easier to form a positive image of Egypt, for the New Testament mentions Egypt explicitly only once, and in an affirmative way. Once again Egypt is a place of refuge, this time from Herod’s persecution of the Holy Family. (Ebeling)

Contrary to the final quote above, the New Testament does not mention Egypt only once. It is also explicitly named in the book of Revelation and the details of that will be discussed in a subsequent section.

The sun is a god

Copernicus previously stated in his book that “Trismegistus calls it [the sun] a ‘visible god.’” This claim is found in Treatise V (5) of the Corpus Hermeticum (part of the Hermetic writings), titled “A discourse of Hermes to Tat, his son: That god is invisible and entirely visible”:

If you want to see god, consider the sun . . . . The sun, the greatest god of those in heaven, to whom all heavenly gods submit as to a king and ruler, this sun so very great, larger than earth and sea, allows stars smaller than him to circle above him. To whom does he defer, my child? Whom does he fear? (Copenhaver)

Treatise XVI (16) continues:

For the sun is situated in the center of the cosmos, wearing it like a crown. Like a good driver, it steadies the chariot of the cosmos and fastens the reins to itself to prevent the cosmos going out of control. (Copenhaver)

Around the sun are the eight spheres that depend from it: the sphere of the fixed stars, the six of the planets, and the one that surrounds the earth. From these spheres depend the demons, and then, from the demons, humans. And thus all things and all persons are dependent from god. (Copenhaver)

In the Asclepius (part of the Hermetic writings, and named after a Greek god who is the son of Apollo) we also read:

There are many kinds of gods, of whom one part is intelligible, the other sensible [visible]. Gods are not said to be intelligible because they are considered beyond the reach of our faculties; in fact, we are more conscious of these intelligible gods than of those we call visible . . . .

. . . these are the sensible [visible] gods, true to both their origins, who produce everything throughout sensible [visible] nature . . . . (Copenhaver)

In fact, the sun illuminates the other stars not so much by the intensity of its light as by its divinity and holiness. The sun is indeed a second god . . . . (Copenhaver)

These texts reveal that there are visible and invisible gods, and that the sun is a second god, of the sensible/visible sort. This is where Copernicus is quoting from, but there is more. Copernicus says “in the center of all rests the sun”; Trismegistus says the sun is “situated in the center of the cosmos.” Copernicus says the sun is “the pilot of the world”; Trismegistus says it is “a good driver.” Copernicus says the sun “governs the family of stars which wheel around”; Trismegistus says “around the sun are the eight spheres that depend from it.”

As previous examples have illustrated, these ideas are congruent with the solar theology of ancient Egypt, and the Hermetic writings are indeed Egyptian:

It should come as no big surprise, therefore, to learn that soon after the introduction of the Hermetica in Europe, the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), inspired by the contents of these sacred books from Egypt’s golden age, formulated a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology . . . . And although Copenicus’s knowledge of mathematics was largely derived from Arabic sources, the now legendary heliocentric model that he proposed was almost certainly inspired by the ancient Egyptian notion of a divine sun being at the center of all things. Indeed, in some passages of the Hermetica, the sun is presented as the demiurge, the “second God,” a term implying that it governed all things on Earth as well as the stars (the constellations and planets)—a poetic and albeit roundabout way of saying that the sun, not Earth, is the focus of the visible universe. (Bauval and Osman)

The Hermetic tradition also had more specific effects. Inspired, as is now known, by late Platonist mysticism, the Hermetic writers had rhapsodized on enlightenment and on the source of light, the Sun. . . . A young Polish student [Copernicus] visiting Italy at the turn of the 16th century was touched by this current. (Williams)

. . . Italy was awash with occult theories about the sun, placing it figuratively, if not literally, at the centre of the universe. . . . it is indicative of the zeitgeist in which he [Copernicus] was educated. We even find the Pole [Copernicus] citing Hermes Trismegistus, who wrote that the sun was a visible god. (Hannam)

Satan disguised

Russian spiritualist and occultist Helena Blavatsky stated the following concerning Thoth and Hermes, the two gods that make up the figure of Trismegistus:

. . . Hermes, the God of Wisdom, called also Thoth, Tat, Seth, Set, and Satan. (Blavatsky)

English historian of the Renaissance Frances Yates also wrote:

The decans appear here [in the Hermetic writings] as powerful divine or demonic forces, close to the circle of the All, and above the circles of the zodiac and the planets and operating on things below either directly through their children or sons, the demons, or through the intermediary of the planets. (Yates)

The name of Hermes Trismegistus was well known in the Middle Ages and was connected with alchemy, and magic, particularly with magic images or talismans. The Middle Ages feared whatever they knew of the decans as dangerous demons, and some of the books supposedly by Hermes were strongly censured by Albertus Magnus as containing diabolical magic. The Augustinian censure of the demon-worship in the Asclepius (by which he may have meant in particular, decan-worship) weighed heavily upon that work. However, mediaeval writers interested in natural philosophy speak of him with respect; for Roger Bacon he was the “Father of Philosophers” . . . . (Yates)

The Bible also tells us that behind new gods that come up you can expect to find Satan and his angels:

Deuteronomy 32:16-17

King James Version

16 They provoked him to jealousy with strange gods, with abominations provoked they him to anger.17 They sacrificed unto devils, not to God; to gods whom they knew not, to new gods that came newly up, whom your fathers feared not.

Egypt, Pythagoras, and Trismegistus

Egypt is a common thread that binds Pythagoras to Trismegistus. Pythagoreanism predates Hermeticism by several centuries and it is the view of scholars that Pythagoreanism (Greek philosophy) in Alexandria, Egypt, facilitated the birth of Hermeticism:

Egyptian ideas had for a long time been carried to Italy, but eventually the opposite movement started—from Italy back to Egypt. It began in a big way when Alexander the Great had the city called Alexandria built at the mouth of the Nile during the late fourth century BC. People in southern Italy and Sicily gave themselves all kinds of reasons for doing what they had to do: emigrating to Egypt.

Pythagoreanism itself had always been a flexible tradition. Its personal demands on anyone who wanted to become a Pythagorean were immense. But, paradoxically, to be a Pythagorean meant belonging to a system that encouraged initiative and creativity: that kept changing, consciously adapting to the needs of different people and places and times.

So when Pythagoreans started arriving in Egypt they didn’t simply set up shop as Pythagoreans. They also started merging their teachings with a tradition that was eminently Egyptian. This was the tradition that belonged to the god Thoth—or, as he came to be called by Greeks in Egypt, Hermes Trismegistus.

The Hermetic texts, or “Hermetica,” that began being produced in Greek were initiatory writings. They served a very particular and practical purpose inside the circles of Hermetic mystics. And many of the methods they describe, as well as a great deal of the terminology they use, are specifically Pythagorean in origin.

But the Hermetica are far more than adaptations of Pythagorean themes. They are also the most obvious manifestation of Pythagoreanism returning to Egypt.

Until not long ago, the occasional references to Egyptian gods and religion in the Hermetic writings were dismissed as superficial veneer: as touches of local color added to the Greek texts to give them the illusion that they contained the authentic wisdom of Egypt. But the Hermetic literature is Egyptian to its core. Even the name “Poimandres” or “Pymander,” the title often given to the Hermetica as a whole, is Egyptian through and through. It’s simply a Greek version of P-eime nte-re, “the intelligence of Re.” And the god who was known in Egypt as the “intelligence” of the sun god, Re, was Thoth—the Egyptian Hermes.

. . .

These were the Egyptian traditions that Pythagoreanism started merging with to become those Greek Hermetica. And you could say that in doing so it was at last coming home. The Greek Hermetic writings weren’t the end of Pythagoreanism’s return to Egypt. On the contrary, they were just the beginning.

Already in the second century BC Greek-speaking Egyptians who lived on the Nile Delta had started receiving Pythagorean traditions on one hand and, on the other, shaping what was to become known as the art of alchemy. Northern Egypt was simply the starting point for a whole process of transmission from West back to East. (Crossing Religious Frontiers)

On the whole, the Hermetic writings can only be understood as syncretism. They are the product of a process of intellectual fusion, as was typical of Graeco-Roman Egypt. (Ebeling)

The main works of alchemy were said to be ancient, written by a mysterious author known as Hermes Trismegistus (“three times great”), a legendary mixture of the Greek god Hermes (Mercury) and the Egyptian god of wisdom. And alchemists [Hermeticists] were secretive, like the cult of Pythagoras. Hence, throughout the centuries, some seekers of alchemical knowledge increasingly suspected that Pythagoras, who allegedly visited Egypt, had been privy to such secrets. (Martinez, Science Secrets: The)

. . . one of the earliest Latin texts on alchemy featured Pythagoras. It appeared in the thirteenth century, translated from Arabic, and tells of a gathering of nine philosophers convened by Pythagoras to clarify obscurities in ancient alchemical books. . . . Pythagoras argued that the philosophers used marvelously varied expressions to convey the same art and to keep hiding the precious art from the vulgar and foolish. (Martinez, Science Secrets: The)

The growing legend of Pythagoras crept into the history of alchemy and chemistry. The association of Pythagoras with the secrets of the Egyptians illustrates the kind of syncretism of Greek and Egyptian myths that is often embodied by the legendary figure of Hermes Trismegistus. In the words of Johannes Kepler, “either Pythagoras hermeticizes, or Hermes pythagorizes.” (Martinez, Science Secrets: The)

Know the sun to become godlike

An earlier quote stressed that Pythagoras “became an intermediary guide to help other philosophers in turn become godlike.” Copernicus also stresses this in his book:

. . . he [Plato] thinks that it is impossible for anyone to become godlike or be called so who has no necessary knowledge of the sun, moon, and the other stars.

However, this more divine than human science, which inquires into the highest things, is not lacking in difficulties. (Copernicus)

Professor of history Alberto A. Martinez elaborates:

Copernicus also discussed [in his book] the allegedly divine significance of the Sun. He noted that Plato had argued that to become godlike one must know the Sun, the Moon and the heavenly bodies. Copernicus added that some people called the Sun the ruler of the universe, that ‘Trismegistus called it a visible god . . . . (Martinez, Burned Alive: Giordano)

The Hermetic writings also reinforce this Pythagorean point:

The abovementioned fundamental interrelationship between God, cosmos and man is based on the idea that the supreme God is the One [Monad], who contains everything and produces everything. This is clearly expressed at the beginning of the Asclepius: “All things are part of the One, or the One is all things.” (Hermes Explains: Thirty)

Only the human being has a twofold nature: mortal because of its material body and immortal because of its divine mind.

This unique human condition was famously hailed by Hermes [Trismegistus] in a formula which became central to the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth century: “For that reason, Asclepius, man is a great wonder (magnum miraculum est homo), a living being, to be worshipped and honoured.” Humans can only return to their divine origin if their immortal part, the mind, takes control over the passions of the body. An important means to achieve this is to contemplate the beautiful order of the cosmos, which inevitably leads to the conclusion that there must be a perfect creator. This idea had already been developed in Stoic [and Pythagorean] philosophy and was to play an important role in later Christian theology, as the cosmological argument for the existence of God. For the Hermetist, though, this was not merely a case of logical thinking but a religious experience. . . .

. . . The Hermetic texts describe two kinds of initiation of which one leads to the experience of being united with the supreme God and the other to that of falling together with the universe (which makes no great difference, because the One [Monad] is everything). . . . the initiate joins the singing powers of the eighth sphere and then they all ascend to the Father and merge in God: “This is the final good for those who have received knowledge: to become God.”

. . .

These ideas are obviously difficult to reconcile with the basic doctrines of Christianity, especially the conviction of a deep divide between God and man. (Hermes Explains: Thirty)

Treatise XI (11) of the Corpus Hermeticum makes this particularly clear:

Thus, unless you make yourself equal to god, you cannot understand god; like is understood by like. Make yourself grow to immeasurable immensity, outleap all body, outstrip all time, become eternity and you will understand god. Having conceived that nothing is impossible to you, consider yourself immortal and able to understand everything, all art, all learning, the temper of every living thing. Go higher than every height and lower than every depth. Collect in yourself all the sensations of what has been made, of fire and water, dry and wet; be everywhere at once, on land, in the sea, in heaven; be not yet born, be in the womb, be young, old, dead, beyond death. And when you have understood all these at once - times, places, things, qualities, quantities - then you can understand god. (Copenhaver)

Long before these traditions, we hear the same tiring trope from Satan in the book of Genesis:

Genesis 3:4-6

King James Version

4 And the serpent [Satan] said unto the woman, Ye shall not surely die:5 For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.

6 And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat.

Judgment upon all the gods of Egypt

When God liberated the Hebrews from the Egyptians, freedom from bondage was only part of his plan of deliverance. He also personally judged all the gods of Egypt:

Exodus 18:9-11

King James Version

9 And Jethro rejoiced for all the goodness which the Lord had done to Israel, whom he had delivered out of the hand of the Egyptians.10 And Jethro said, Blessed be the Lord, who hath delivered you out of the hand of the Egyptians, and out of the hand of Pharaoh, who hath delivered the people from under the hand of the Egyptians.

11 Now I know that the Lord is greater than all gods: for in the thing wherein they [the Egyptians] dealt proudly he was above them.

What was this prideful “thing” Jethro speaks of? Other passages state:

Numbers 33:3-4

King James Version

3 And they departed from Rameses [the Egyptian king] in the first month, on the fifteenth day of the first month; on the morrow after the passover the children of Israel went out with an high hand in the sight of all the Egyptians.4 For the Egyptians buried all their firstborn, which the Lord had smitten among them: upon their gods also the Lord executed judgments.

Exodus 12:12-13

King James Version

12 For I will pass through the land of Egypt this night, and will smite all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgment: I am the Lord.13 And the blood shall be to you for a token upon the houses where ye are: and when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and the plague shall not be upon you to destroy you, when I smite the land of Egypt.

The Egyptians had thousands of gods. This was a thing they dealt proudly in:

Egypt had one of the largest and most complex pantheons of gods of any civilization in the ancient world. Over the course of Egyptian history hundreds of gods and goddesses were worshipped. The characteristics of individual gods could be hard to pin down. Most had a principle association (for example, with the sun or the underworld) and form. (Britannica, “11 Egyptian Gods”)

The gods and goddesses of Ancient Egypt were an integral part of the people’s everyday lives for over 3,000 years. There were over 2,000 deities in the Egyptian pantheon . . . . (Mark, “Egyptian Gods - The”)

The ancient Egyptians worshipped over 1,400 different gods and goddesses in their shrines, temples, and homes. These deities were the centre of a religion lasting over three thousand years!

Many of the Egyptian gods and goddesses were anthropomorphic, which means that they were usually depicted as part human and part animal. Can you think of anything that might be anthropomorphic? (“Gods of Egypt”)

One of the plagues sent to Egypt involved the blotting out of the sun, their chief god and highest object of worship:

Exodus 10:21-23

King James Version

21 And the Lord said unto Moses, Stretch out thine hand toward heaven, that there may be darkness over the land of Egypt, even darkness which may be felt.22 And Moses stretched forth his hand toward heaven; and there was a thick darkness in all the land of Egypt three days:

23 They saw not one another, neither rose any from his place for three days: but all the children of Israel had light in their dwellings.

Images of man, birds, beasts, and creeping things

In the book of Romans, Paul speaks of a group that witnessed the power of God, knew him, but refused to retain him in their knowledge:

Romans 1:20-25

King James Version

20 For the invisible things of him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even his eternal power and Godhead; so that they are without excuse:21 Because that, when they knew God, they glorified him not as God, neither were thankful; but became vain in their imaginations, and their foolish heart was darkened.

22 Professing themselves to be wise, they became fools,

23 And changed the glory of the uncorruptible God into an image made like to corruptible man, and to birds, and fourfooted beasts, and creeping things.

24 Wherefore God also gave them up to uncleanness through the lusts of their own hearts, to dishonour their own bodies between themselves:

25 Who changed the truth of God into a lie, and worshipped and served the creature more than the Creator, who is blessed for ever. Amen.

26 For this cause God gave them up unto vile affections: for even their women did change the natural use into that which is against nature:

27 And likewise also the men, leaving the natural use of the woman, burned in their lust one toward another; men with men working that which is unseemly, and receiving in themselves that recompence of their error which was meet.

28 And even as they did not like to retain God in their knowledge, God gave them over to a reprobate mind, to do those things which are not convenient;

This is a passage that finds an astonishing fulfillment in ancient Egypt. Pharaoh’s response to the first miracle he witnessed from God was to immediately summon his wise men in defiance, professing themselves to be wise:

Exodus 7:8-12

Modern English Version

Aaron’s Rod Becomes a Snake

8 Now the Lord spoke to Moses and to Aaron, saying, 9 “When Pharaoh shall speak to you, saying, ‘Show a miracle,’ then you shall say to Aaron, ‘Take your rod, and throw it before Pharaoh,’ and it shall become a serpent.”10 So Moses and Aaron went to Pharaoh, and they did what the Lord had commanded. And Aaron threw down his rod before Pharaoh and before his servants, and it became a serpent. 11 Then Pharaoh also called the wise men and the sorcerers. Then the magicians of Egypt likewise performed with their secret arts. 12 For every man threw down his rod, and they became serpents. But Aaron’s rod swallowed up their rods.

Many of the gods of the Egyptians were anthropomorphic or amalgamations of man with birds, beasts, and other animals. They also worshiped creeping things like the scarab/dung beetle and snake:

Even odder were the many Egyptian gods, with bodies in human shape and heads of animals – inverted centaurs and satyrs. (Copenhaver)

The predominant characteristics of much of Egyptian religion were animism, fetishism and magic. There was also the belief that certain animals possessed divine powers – the cow, for example, represented fertility, the bull virility – which led to the cult of sacred animals, birds and reptiles, each of which was considered to be the manifestation on earth of a divine being. It was this aspect of Egyptian religion more than any other that the Greeks found curious and the Romans horrifying. Both Greeks and Romans were happy about the polytheism, being polytheistic themselves. However, their own gods, although they were celestial, immortal beings, were nevertheless recognizably human: they had human shapes, and were possessed of human emotions and frailties. But the Egyptian gods! The most cursory look at reliefs carved on temple walls showing representations of gods revealed one with the body of a man and the head of a hawk; another with the body of a man and the head of a jackal. Yet another man seemed to have a beetle in place of a head, while the woman standing next to him had the head of a lioness. They were all gods; and so were the vultures and cobras hovering in attendance on them.

Inside the temples, the Egyptians kept real live cats, bulls, ibises or hawks, and worshipped them as gods; and when they died, mummified and buried them as they did their kings. The Roman satirist, Juvenal, exclaimed:

Who does not know, Volusius, what monsters are revered by demented Egyptians? One lot worships the crocodile; another goes in awe of the ibis that feeds on serpents. Elsewhere there shines the golden effigy of the sacred long-tailed monkey.

Juvenal would perhaps have been even more scornful had he realized the number and diversity of the gods worshipped by Egyptians, who had created hundreds of deities, probably more than any people before or since. (Watterson)

Middle Kingdom [Egyptian] rulers already claimed to rule “all which the sun disk encircles,” an expression of universal domination that remained popular through the New Kingdom. During the reign of Akhenaten, the word for disk became the name of the solar deity, which we signal through the capitalization of “Aten.” Amunhotep IV’s royal predecessors in the Eighteenth Dynasty manifested as the sun disk, brightening the two lands. . . .

While Amunhotep IV’s representation of the sun god as a shining disk may seem an obvious choice to us, it was not an expected form for a god to take in ancient Egypt. On the walls of temples and tombs, in statuary, and on privately owned objects, deities generally assume three possible forms: fully anthropomorphic; human-bodied with animal heads; or fully zoomorphic. The hybrid animal-human representation is the one that the non-Egyptian world has viewed as the most characteristically—even caricature-ishly—“Egyptian” since the days of ancient Rome. Artists avoided a monstrous marriage of human and animal through the addition of a large wig, which smoothed the transition between species. Re [the sun god] manifested in a great many forms, including the scarab beetle, Khepri, whose very name means “manifesting one” or “he who transforms.” The most common form of Re was as a man or falcon-headed man crowned by a disk. Yet this standard representation was only one among many within the richness of Egyptian religious iconography. (J. Darnell and C. Darnell)

Atum is usually represented as a man wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, although he could also be portrayed as a snake. Other animals deemed sacred to him were the lion, bull, ichneumon, lizard and dung beetle. (Wilkinson)

The biblical passage also states that this group dishonored their own bodies between themselves, burning with lust for what is unnatural. In a book aptly titled “In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians,” Egyptologist Charlotte Booth writes:

The ancient Egyptians themselves acknowledged women in same-sex relationships, in particular, in the dream interpretation books, which offered a positive or negative interpretation for any dream. Papyrus Carlsberg states: if a woman ‘dreams that a woman has intercourse with her she will come to a bad end’. However, this alone cannot be used as evidence that female homosexuality was considered negative, as Papyrus Carlsberg XIII, currently in Copenhagen, lists a number of sexual dreams of women, the majority of which were considered a negative omen. The only positive sexual dreams were

If a ram has intercourse with her, Pharaoh will be benevolent towards her,

If a wolf has intercourse with her, she will see something beautiful,

If an ibis has intercourse with her, she [will] have a well-equipped house. (Booth)

From a young age, boys would have been aware of homosexuality, as it was considered such a normal if not necessarily acceptable part of everyday life, that it was a prominent element in religious mythology. The myth known as the Contendings of Horus and Seth is the tale of the conflict between Seth, the god of chaos, and his nephew, Horus the god of order. Seth wanted to take the throne of Egypt, following the murder of his brother Osiris, from the rightful descendent, Osiris’s son Horus. This conflict ends in an eighty-year tribunal, and in various incidents, including sexual, between the two deities. The homosexual encounters that took place between Horus and Seth are always instigated by Seth, the god of chaos, with Horus as the recipient . . . . (Booth)

Depictions of men embracing is not particularly unusual in a royal context, and in the Middle Kingdom temple of Senusret I and the White Chapel at Karnak the king is shown numerous times embracing the god, oftentimes the ithyphallic deity Amun-Min. . . . In these scenes, the god is completely covered in a cloak with only his erect penis protruding from the front, indicating this was an important element of the cult.

. . . These images essentially demonstrate the king (a male) worshipping the fecundity of an erect penis. (Booth)

. . . homosexuality or same-sex relationship was a part of Egyptian life, so much so that it was included in religious texts, literary texts and poetry. However, as mentioned, homosexuality did not have the necessary lifestyle choices or associations that it does in the modern world, and Parkinson has suggested that to ancient Egyptians: ‘Sexual preferences were acknowledged but only as one would recognise someone’s taste in food’. (Booth)

The interpretations for dreams about sex were different for a woman as we learn from the Demotic papyrus Carlsberg XIIb:

If a woman dreams she is married to her husband, she will be destroyed. If she embraces him she will experience grief.

If a horse has intercourse with her, she will use force against her husband.

If a donkey has intercourse with her, she will be punished for a great sin.

If a he-goat has intercourse with her, she will die soon.

If a Syrian has intercourse with her, she will weep for she will let her slaves have intercourse with her.. . . The dreams are a little odd, to say the least, to the modern mind. However, it needs to be considered that many of the animals featuring in these dream interpretations were avatars of specific gods. (Booth)

This most certainly confirms that sexuality was a prominent theme in Egyptian culture, matching the details in the biblical passage. Egyptian texts even contain casual references to bestiality in the reading of dreams. The creator and sun god Atum also brought forth all created things via a sexual act:

The act of masturbation is also only referred to in religious texts where the creator god Atum masturbates in order to create the next generation of gods . . . . (Booth)

The Egyptians could describe creation through intellectual means—thought and speech—or physical actions, like the masturbation of a creator deity. In all ancient Egyptian creation accounts, the unifying theme is how order and multiplicity emerge from an undifferentiated oneness. The creator god contained within himself the possibility of all beings. In artistic representations the default image of a creator deity is an adult male, but other options did exist. The sun god Re can take the form of a scarab, literally the “transforming one,” or a baby, reborn each day. (J. Darnell and C. Darnell)

The creator god held within himself millions, the potentiality of everything: all gods, all people, all animals, all plants, the stars in heaven and the minerals of the earth. He, for the Egyptian conventionally called him such, was also androgynous, having male and female attributes. In the sexually charged creation myth of Iunu, Re-Atum masturbated, the male phallus brought to orgasm by the female hand, and from that act Shu and Tefnut were brought into existence. . . . What unifies every ancient Egyptian creation account is that the one becomes many, until all of creation is complete. (J. Darnell and C. Darnell)

The book of Revelation also mentions Egypt, beside Sodom, instead of the usual Gomorrah:

Revelation 11:8

King James Version

And their dead bodies shall lie in the street of the great city, which spiritually is called Sodom and Egypt, where also our Lord was crucified.

Like Egypt, Sodom was guilty of similar sins:

Jude 7

King James Version

Even as Sodom and Gomorrha, and the cities about them in like manner, giving themselves over to fornication, and going after strange flesh, are set forth for an example, suffering the vengeance of eternal fire.

Spiritually, Revelation 11:8 implies unfaithfulness and going after strange gods/beliefs. We can include the Egyptian/Pythagorean/Hermetic beliefs we have reviewed so far in this category.

Egypt is also particularly interesting because it predates the great city of Babylon, which is also employed as a symbol in the book of Revelation. It helps to keep this in mind when tracing the chronology and origin of certain ideas:

Ancient Egypt, civilization in northeastern Africa that dates from the 4th millennium BCE. (Baines et al.)

Babylon, one of the most famous cities of antiquity. It was the capital of southern Mesopotamia (Babylonia) from the early 2nd millennium to the early 1st millennium BCE and capital of the Neo-Babylonian (Chaldean) empire in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, when it was at the height of its splendor. (Saggs)

In its original form, before the emergence of the state, religion consisted in the worship of Nature as the sole deity. With the creation of the state, this original monotheism of Nature had to be turned into a mystery religion and practiced in secrecy, because the state had to be founded on a quite different religious system. Egypt, which was held to be the first state in the sense of a large-scale political organization in the history of mankind, presented the model for this double religion, which was followed by all the other nations: an official, public polytheism, and a mystery religion with secret rites and an arcane monotheistic or pantheistic theology, which then became the matrix of all other mystery cults. (Assmann)

Ancient Egypt practiced a peculiar form of monotheism and simultaneous pantheism (in a practical sense, it was just pantheism). How they treated their sun god provides glimpses of this, but more will be discussed in a future study and its relation to the Roman Catholic doctrine of the Trinity.

The Roman Catholic Church

Copernicus could not have done what he did without a nudge and support from the Roman Catholic Church. He writes in his book:

. . . my friends made me change my course in spite of my long-continued hestitation and even resistance [to publish my book]. First among them was Nicholas Schonberg, Cardinal of Capua, a man distinguished in all branches of learning; next to him was my devoted friend Tiedeman Giese, Bishop of Culm, a man filled with the greatest zeal for the divine and liberal arts: for he in particular urged me frequently and even spurred me on by added reproaches into publishing this book and letting come to light a work which I had kept hidden among my things for not merely nine years, but for almost four times nine years. (Copernicus)

Other scholars admit this important point:

With the blessing of the church, which he served formally as a canon, Nicolaus Copernicus set out to modernize the astronomical apparatus by which the church made such important calculations as the proper dates for Easter and other festivals. (Williams)

. . . Copernicus was a canon in the Roman Catholic Church and high dignitaries of that Church were associated with the publication of his book. (Butterfield)

Although at first Aristotelians and conservative theologians found the Copernican theory outrageous, the educated papal authorities had a deep interest in science and recognized the explanatory power of the Copernican theory. (Zack)

In a paradoxical and out-of-character move, the Church would later denounce the work of Copernicus as “the false Pythagorean doctrine,” an admission as to its origin. The trajectory of these events is quite lengthy to follow and will require a separate study. Egypt, Pythagoras, and Trismegistus will make another appearance there:

In 1616, the Holy Congregation denounced “the false Pythagorean doctrine, altogether contrary to Holy Scripture.” The cardinals concluded that the proposition of a stationary sun is “foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture, according to the literal interpretation of the words.” Therefore, the sun-centered theory could not be defended or held. The Holy Congregation promptly banned the books of Copernicus . . . . (Martinez, Science Secrets: The)

Pythagoreanism everywhere

Given the primacy of Pythagoreanism as one of the earliest forms of Greek philosophy, inevitably, it influenced subsequent philosophical movements. These movements may not have taken up the Pythagorean name, but they continued Pythagorean themes. One notable example is the philosophy of Plato:

Indeed, the Pythagorean school was the leading school of astronomy in that century [fifth century B.C.] and the most progressive. Their mathematical mysticism had its useful side, for it helped to assume regularities in the celestial motions and to discover planetary laws. . . .

When we speak of Pythagorean astronomers, we do not mean only those who were fully initiated in all the Pythagorean mysteries, but also those who accepted, if only in part, the Pythagorean views on the system of the world. . . .

The Pythagoreans were the first to call the world cosmos (implying that it is a well-ordered and harmonious system) and to say that the earth is round. . . . By that time [middle of the fifth century B.C.], some points of Pythagorean cosmology were already determined; the universe is a well-ordered system; the most perfect shape is the sphere and the earth is round . . . . (Sarton)

During his [Pythagoras] time at Croton he founded a semi-religious community, which outlived him until it was scattered about 450 BC. He is credited with inventing the word ‘philosopher’: instead of claiming to be a sage or wise man (sophos) he modestly said that he was only a lover of wisdom (philosophos). The details of his life are swamped in legend, but it is clear that he practised both mathematics and mysticism. In both fields his intellectual influence, acknowledged or implicit, was strong throughout antiquity, from Plato to Porphyry.

. . .

Pythagoras’ philosophical community at Croton was the prototype of many such institutions: it was followed by Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, Epicurus’ Garden, and many others. Some such communities were legal entities, and others less formal; some resembled a modern research institute, others were more like monasteries. (Kenny)

The history of the projection of Pythagoreanism into subsequent thought indicates how fertile some of its core concepts were. Plato is here the great catalyst; but it is possible to perceive behind him, however dimly, a series of Pythagorean ideas of paramount potential significance . . . . (Thesleff)

This mystical element entered into Greek philosophy with Pythagoras, who was a reformer of Orphism, as Orpheus was a reformer of the religion of Bacchus. From Pythagoras Orphic elements entered into the philosophy of Plato, and from Plato into most later philosophy that was in any degree religious. (Russell)

Egypt, Pythagoras, and the central Hearth fire also became important symbols to later intellectuals, revolutionaries, and secret societies:

Things Egyptian were often associated with the prisca theologica [ancient theology or wisdom]. It was known in Renaissance Europe that Egypt was the oldest ancient civilization, and that the ancient Greeks themselves had viewed Egypt as a source of mystical wisdom. (Burns)

Egypt, this “image of heaven,” this “temple of the world,” as it is called in the Asclepius, thus became the almost mythically overrated origin of all divine wisdom and human pious practices. (Ebeling)